In recent years, memes have become a much used and discussed medium on the internet. Memes are expressed mannerisms, traits or ideas that are often reproduced through a specific pattern[1]. They can be used to describe a vast set of expressions, be it videos, gifs, or edited pictures and texts. The term meme was coined by Richard Dawkins in his book The Selfish Gene (1976, 192), where it is described as a tool for forwarding culture from one generation to the next through learned and repeated behavior. While the meaning and use of the term still contains a large spectrum of possibilities, most memes share a comedic, entertaining and storytelling character.

From the perspective of sociologist Erving Goffman (1967, 5–11), memes can in their nature be a response to our interactions with everyday life. While we constantly shape our social performance based on the people we interact with, we strive to maintain a coherence in our presentation. Most importantly, we avoid being met with humiliation or embarrassment, since it challenges the face we maintain for our performance. Losing face is equivalent to losing your stance, pride and conviction as you know it.

Performance- wise, memes follow and are influenced by one another, aiming to build upon specific patterns that have been established for meme culture. If a meme is performed, it is often readapted using the same script, or keying. Keyings in this sense can be seen as significant phrases or actions used to give meaning to the social interaction unfolding (Goffman, 1974, 43-45). If we look at a meme as a performance, a key point in that performance serves as the meme’s bottom line. For example, remaking the “distracted boyfriend / Man looking at another woman” meme requires the three main characters of the original meme, the “you know I had to do it to em” meme needs the person standing with their hands clenched together. These crucial elements serve as keys that convey the story the meme builds on.

Memes, like any interaction on the internet, also still exist in the same social frameworks of society,

aiming to seek approval and “keep face” with a maintained, recognized performance. But given the

anonymity of the internet, it provides you with a huge amount of tools to maintain face, changing

our masks, and changing roles completely if we aren’t satisfied with the image we create of

ourselves. The anonymity can give the actors behind the memes less need to worry about facework.

This, in turn, can give way for the actors to instead use the platform to more freely challenge and

disrupt it’s otherwise maintained coherence. In this sense, the internet can also be seen as a sort of

backstage to society, where everyone laughs, cries or rants about the performances they’ve seen or

acted out. Thus, the vast individualized yet collectively communicating audience on the internet can

view meme performance not with the intent to uphold the face of the person presented or alluded to

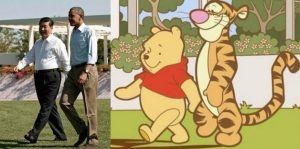

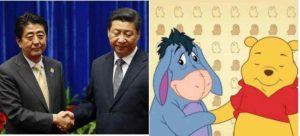

in the meme, but to actively challenge their facework and embarrass them. An interesting example

of this are the Winnie The Pooh memes that relate to the president of Chinas ruling communist

party, Xi Jinping. The memes have actively been comparing Jinping to the honey-loving bear since

2013, with an apparent effort to ridicule the president.

Photo credit: Twitter / @Hong Kong Free press

Photo credit: Twitter / @Hong Kong Free press

Photo credit: Weibo

Photo credit: Weibo

Photo credit: Reuters/Twitter

Photo credit: Reuters/Twitter

What all these memes share is having pictures of Jinping recreated with Winnie The Pooh. The recreation emphasizes having Pooh posing in the same way as Jinping, often down to body language and facial expressions. Additional characters being mimicked in the pictures are common, but not necessary to recreate the meme, as the middle picture shows only Jinping in his car. The keyings in these pictures are Pooh himself- without the bear, the memes would lose their meaning. But Why Pooh? What is going on in this frame?

Firstly, the keying is not only recreating Jinping, but rather his role as the president. Presenting the pictures side by side creates an inevitable comparison between the two characters, asking the audience to spot the difference. Is it Jinping the lovely bear or Pooh, the ruler of the communist party? The role of the president does not only seem to be swapped, however, but recast entirely. This can be interpreted through the positioning of the pictures; all three pictures show the president first and Pooh second. The order portrays the president as the original and Pooh as the follow-up. The meme’s performance tells us “here is the president”, while the keying states that “he is actually, or might just as well be Winnie The Pooh”.

Secondly, the meme is comparing Jinping’s performance as president to Pooh. It’s not just the role as president, it’s how you do it that is shown through Pooh. Initially, Pooh is performing the exact same actions as the president. But Pooh’s characteristics create a humorous contrast; His round design and relaxed expression portray him as adorable, carefree and harmless. Instead of a big, eccentric black vehicle, Pooh drives a plucky, green toy car. Pooh is cute and giddy in his own right, but these traits paint a sharp contrast with the preestablished knowledge we have regarding the role of a president. The performance of a president is expected to be anything but carefree and nonserious, but rather stern, authoritative and determined. Mimicking the exact same actions as the president, Pooh traits in relation to Jinping turns the performance into a mockery.

The meme is telling the audience that it does not take the president seriously. And as it puts the president the face of ridicule, it challenges Jinping’s facework. With the meme becoming popular, shared and recreated, the audience are both reestablishing their image of the president based on the meme’s performance, as well as using it as an outlet to criticize him. This has inevitably lead to the president taking action to not lose his face; The Chinese government has repeatedly censored pooh-related memes on social media and stated that they are a threat to the dignity of their president. The above picture of Pooh and the president in their respective cars serves as the most censored picture of 2015[1]. Winnie The Pooh has since been included in the governments blacklist, and as of 2018, the newly released Disney film Christopher Robin has not been allowed any screenings in China[2].

Whether the President of China has lost his face or is working to maintain it might still be up for debate. However, it’s clear that through challenging his facework, the Winnie The Pooh memes have become a creative and insightful tool for critical thought regarding his presidency. Memes are as such a comedic reaction to our everyday-life, but also a form of activism to challenge the framework around it.

Aino Jauhiainen, kirjoittaja opiskelee kriminologiaa Helsingin yliopistossa

Sources

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. Harvard University Press.

Goffman, E. (1967). Interaction ritual: essays on face-to-face interaction. New York: Anchor Books.

Dawkins, Richard (1989), The Selfish Gene (2 ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-286092-7,

[1] https://globalriskinsights.com/2016/03/china-blacklists-winnie-pooh/

[2] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/aug/07/china-bans-winnie-the-pooh-film-to-stop-comparisons-to-president-xi

[1] https://twobeannouncedsoc.wordpress.com/2015/04/23/the-sociology-of-memes-the-performance-of-internet-culture/